Game Dev Tycoon (GDT) stars you, as a wannabe indie dev with big dreams.

From their site: Replay gaming history. Create best selling games. Research new technologies. Become the leader of the market and gain worldwide fans.

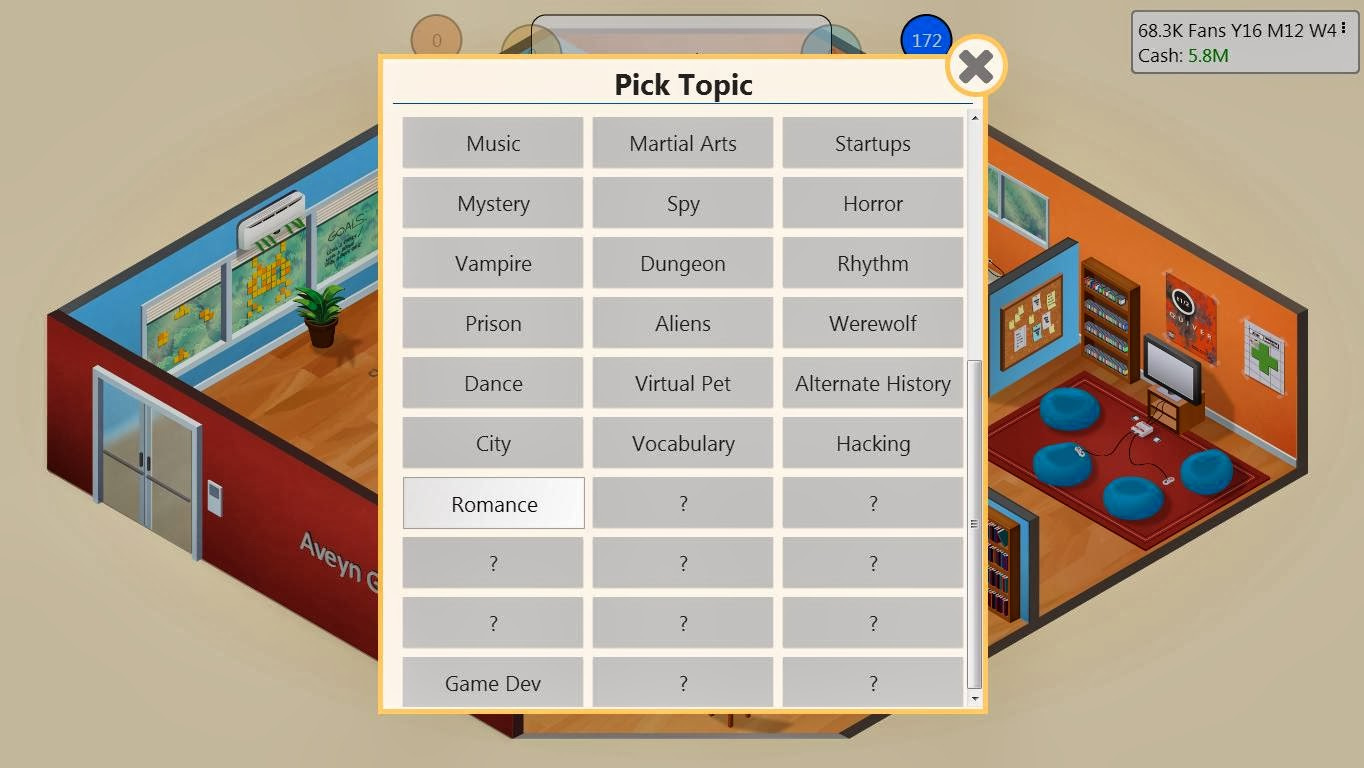

You start by developing smaller games, which have only a handful of decisions to make. You choose the Genre and Topic of your game, and the Platform on which to release.

You then decide how to allocate development time for specific game features, and gather Technology and Design points (more is better). After you release your game, you get reviews, which will impact your sales. With sales money, you expand, building new game engines and bigger games.

GDT trains you to fixate on the review stage. Each of the numbers randomly cycle through a range close to your true score, kind of like a spinner, before settling on a number. It’s immensely satisfying when you see high numbers that don’t fluctuate much; it’s like the critics don’t even need to deliberate, your game is just that good. Because GDT does such a fantastic job rewarding you, you’re entirely beholden to those 4 numbers.

It’s unfortunate, then, that these scores depend largely on your previous reviews. This fact is not made known to you. You’re left wondering why you received such mediocre reviews for a game that should be a bestseller as well (I made two Action games with similarly high Tech/Design scores, they should do about the same, right?). I was left shaking my head a couple times, but was able to pick up on the pattern eventually. And I confirmed this via the wiki

This is a gross oversimplification of an extremely complicated game. You receive bonuses based on a variety of other factors like Audience/Platform match, and even if you don’t get good reviews, you can still get enough money to make profit. But what this means is if you score extremely well compared to your previous games, you’ve made it that much harder for you in the future. It seems like a penalty for what should instead be a reward.

There’s this mechanic called Boost which boosts your productivity temporarily, effectively buying you more dev time. It costs valuable research time, and I can’t see the use for it, because you’re just raising the bar higher for yourself. It’s like purposely raising a heroin addict’s tolerance, so that it takes more and more to achieve the same effect.

This really boils down to clarity in gameplay. The effects of your decisions should be clear enough so that the gameplay challenges and interests you, so that your choices create meaningful tradeoffs or situations. On the flip side, you shouldn’t be bombarded with information, to the point where the decision is reduced to plugging in variables and solving for optimal results, or some other rote action.

GDT doesn’t manage clarity successfully to provide meaningful decisions. In GDT, when you create a new game, you either have prior knowledge of the best path of decisions, or you don’t. When you don’t, it’s about guessing what you think would make sense for certain genres of games, and hoping you and the game designers think alike. The optimal strategy revolves around extreme bookkeeping, which is boring.

Additionally, the many factors make it difficult to ascertain the individual utility of a single action. GDT gives you hints like “Zombie/Action is a great Topic/Genre combo!”, and records previous choices that worked out well for you. However, the effects of the most frequent and important decision of how to allocate development time are presented ineffectually. Let me break it down.

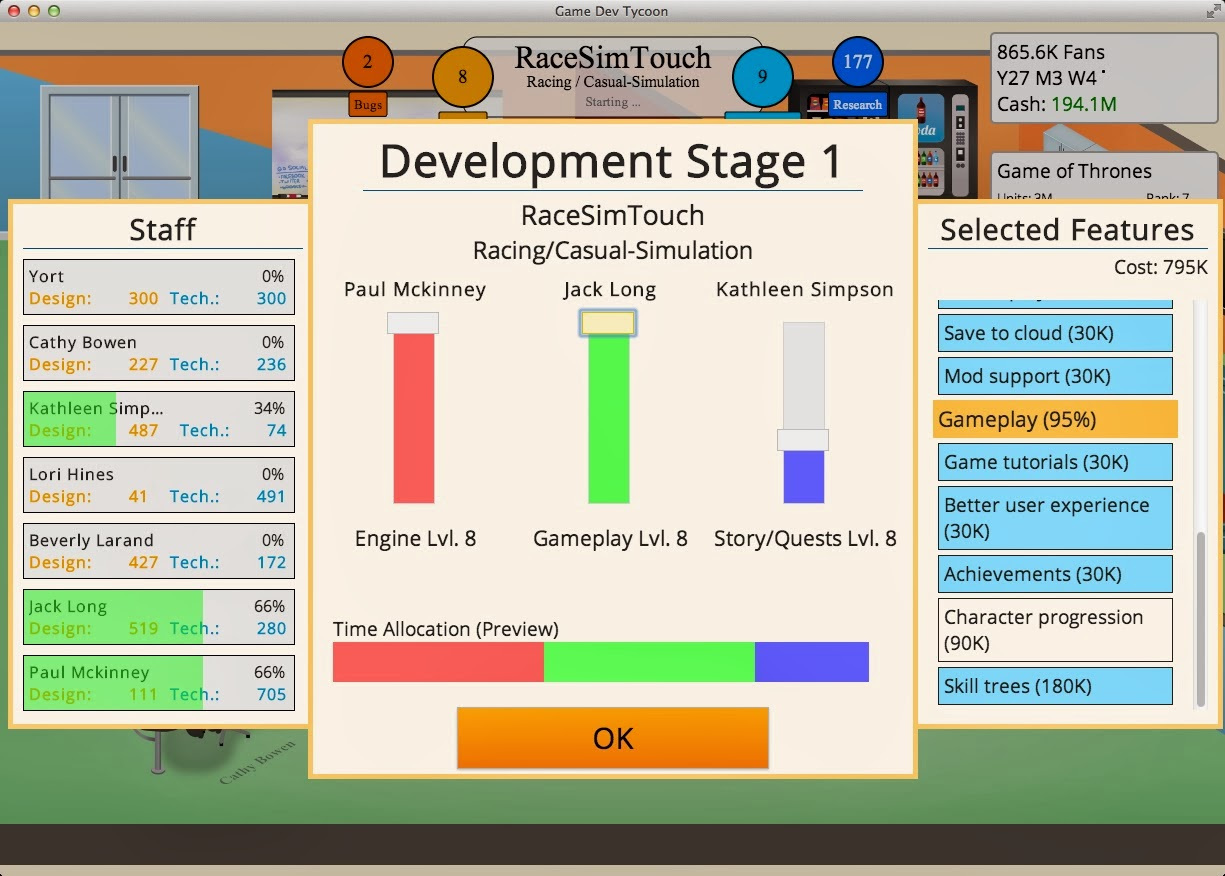

So I’m developing a new game, and I need to decide which of my employees will work on the game engine, and how much time I’ll allocate for that. I’d like to be able to accurately gauge which of my employees is best suited to work on that bit. I choose a heavily tech-focused employee called Paul, and I see his contribution in the form of floating numbers representing Tech and Design points. Seems like lots of bubbles are popping up, so I guess that’s good. But afterwards, my game gets shitty reviews. What the heck? There are any number of possible reasons, all of which are opaque:

1) Paul wasn’t the best employee you could have chosen. Paul needs design chops, because his contribution when working on a game engine depends slightly on his design skills as well. Each feature like Gameplay/Engine/Level Design has a hidden ratio of how much an employee’s design/tech skills contribute. For example, an employee working on the game engine will spend 80% of the time you allotted using his/her Tech skill, and the other 20% on Design. This means slightly more design-focused employees might have produced higher total output.

However, this would be extremely difficult for you to gauge, because all you get in the form of metrics are floating numbers. GDT could have easily presented a nice sum of each of your employees’ contributions afterwards. But that’s not a great solution, because it just means throwing more numbers at you. A better way would have your employees express emotions through facial expressions or dialogue that shows how much they enjoy their work. This would give you a decent indicator of how optimally you are using their skillset.

2) You missed the mark on the Tech/Design ratio for your genre. These ratios exist behind the scenes, but are not hinted at. Some genres require design-heavy development decisions, such as RPGs. So you may have focused way too much on tech instead, and so got shitty reviews.

3) Your Topic/Genre combination sucked ass. You’d think a Superhero/Adventure game would be awesome, but you’re wrong, because the game designers said so. This doesn’t happen too often, but when it does, you’re just like “wtf, lame.”

4) You didn’t spend enough time on AI, which is especially important for certain genres of games like Simulation. This one isn’t too opaque, because GDT does let you know when you screwed up in this manner. But then, it just becomes a question of bookkeeping again.

5) As I mentioned earlier, you might have done well, even close to your top score, but that’s not enough. You need to do significantly better to get those 10’s. It’s such an egregious mishandling of player information.

So I actually think the simulation and algorithm GDT uses is pretty clever, but the presentation was the issue. The tech/design ratios for each genre could have been hinted at in a non-obtuse manner by having playtesters or a QA team give feedback during development. So long as it’s not too heavy-handed, these hints would make you feel great for deciphering the meaning behind audio/text cues. The hidden ratio behind development features could have been handled similarly.

In a world where I had perfect knowledge of every situation in GDT, it wouldn’t be much fun. That’s to be expected though, and certainly not an appropriate mindset in which to design a sim game. Conversely, hiding too much information makes the player feel the simulation is unfair or nonsensical. GDT tends to bounce between these two extremes, without achieving a nice balance. It would either force you into situations where bookkeeping was essential, or provide too little information for you to understand the effects of your actions. This was certainly my experience with GDT; I was getting played by the game; I wasn’t playing it.